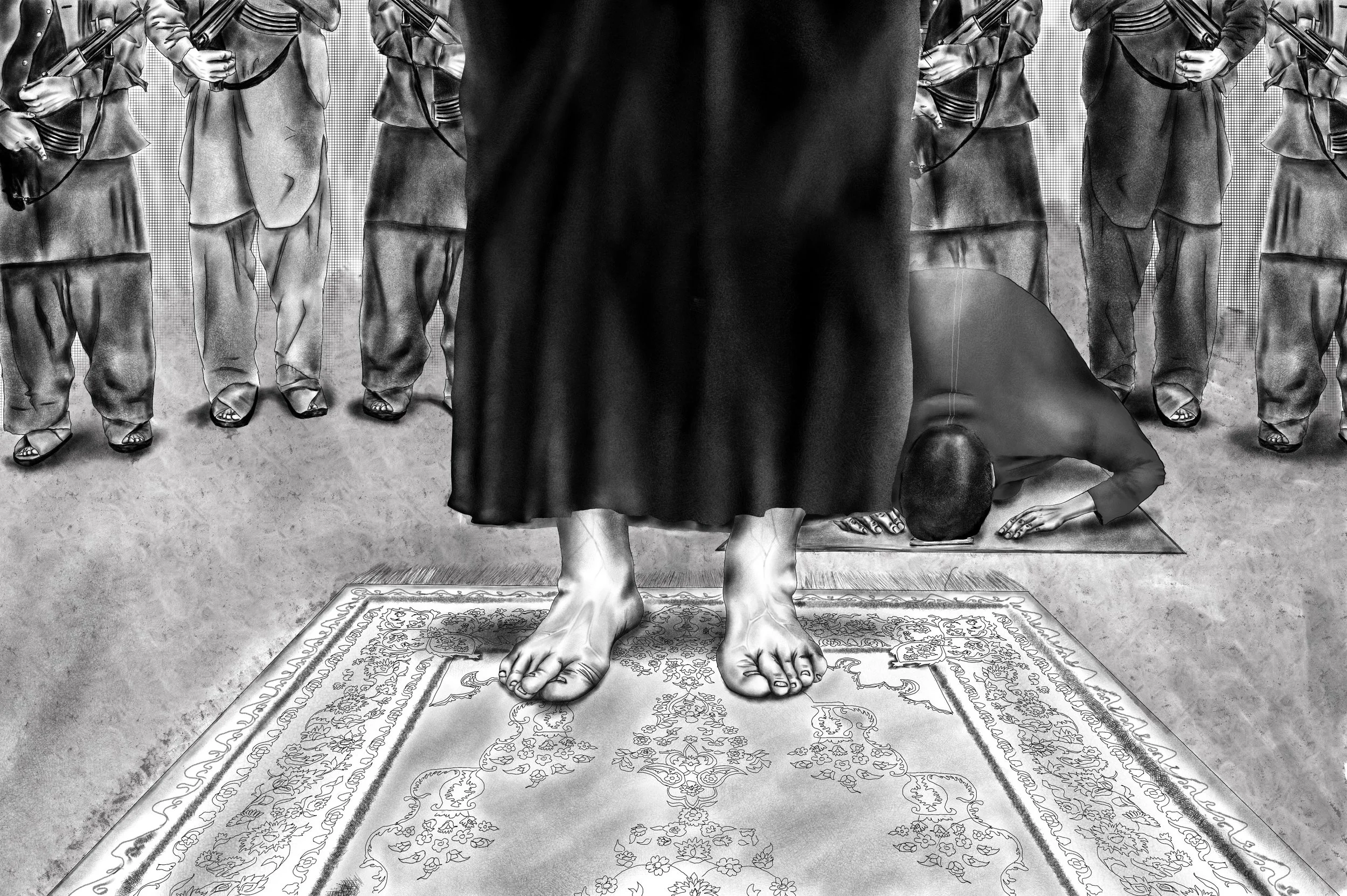

Being An Atheist in the Islamic Republic of Pakistan (or: a Letter to Ammi)

Illustration: Hisham Rifai

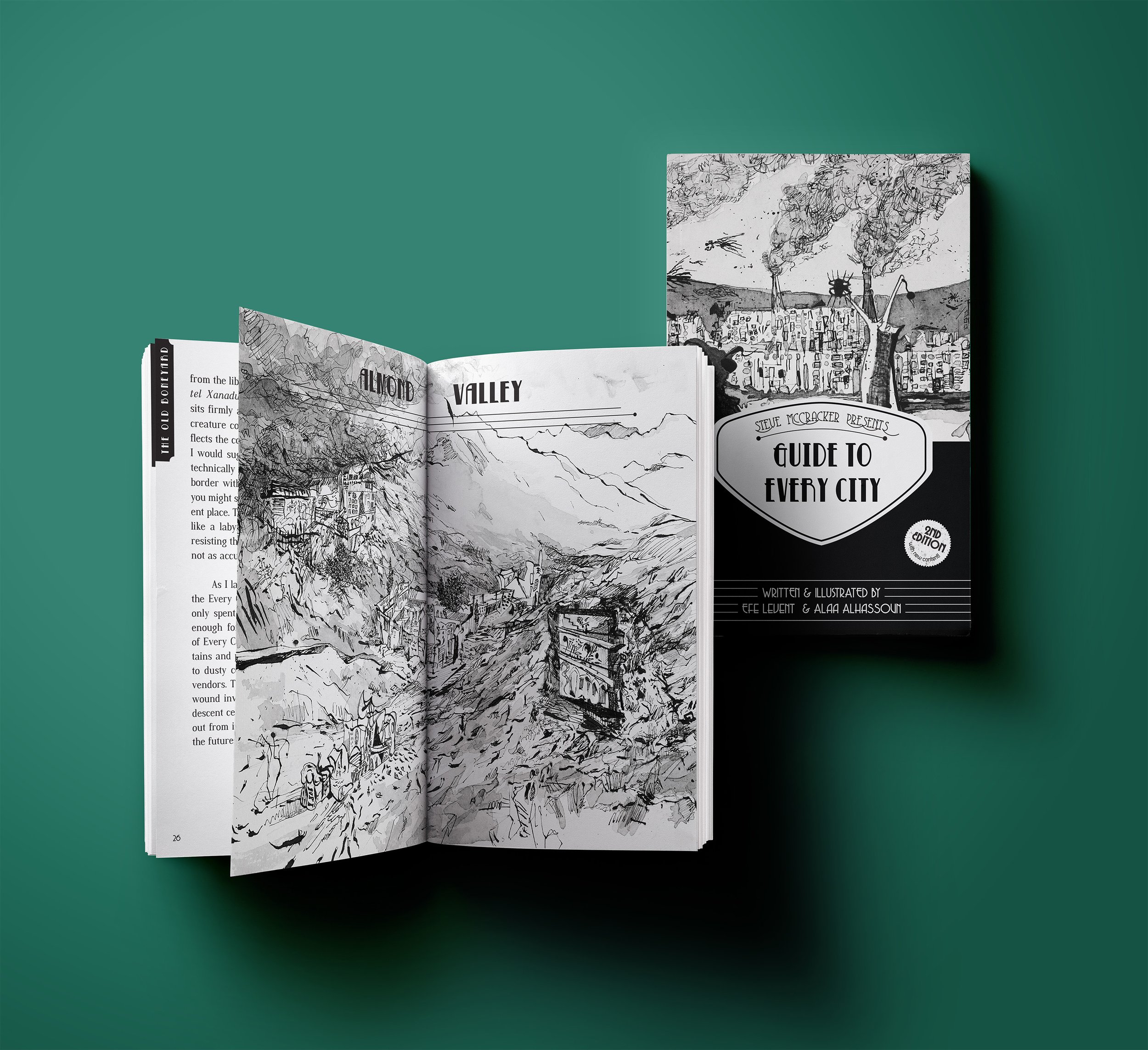

Visit our Bookstore

〰️

Visit our Bookstore 〰️

Written by Efe Levent and illustrated by Alaa Alhassoun, Guide to Every City is a guide for a fictional city inhabited by insects. The three different species of insect in Ever City: hopsters, sloggers, and buzzies live segregated lives in their isolated neighbourhoods. The book not only presents a commentary on social divisions within urban life it also satirises orientalism in contemporary travel writing. The fictional author of the guide -Steve McCracker- is a thoroughly unrelatable hipster who genuinely believes that the rest of the world did not exist until he "discovered" it for some overdesigned travel magazine. You will laugh you will cringe, in the words of Steve: you will "never be the same again."

Ammi,

I couldn’t think of a word to put before your name. Dear, you are to me, but I doubt you’d like an English prefix to your name; its Urdu alternative, pyaari, you would be disgusted by. Mine, - meri - you are, but I often find myself doubting that you would comfortably own that either. With assurance, all I can call you is Ammi.

When I was born, you gave me the title: Syed Muhammad Haider Reza Rizvi. It’s the longest name I know anyone to have, and it shows its whole self on my National ID Card, where my friends only use their first and last name. (We often joke about how I could pass for a jihadist on my resume alone.)

Given your law degree, I’m certain this letter would be unsatisfying without a wall of definitions, so here goes:

Syed is a title given to Prophet Muhammad’s (PBUH) descendants, (I couldn’t write it without a “(PBUH)”, even if I tried) especially those through Imam Hussain (A.S.). You’ve taught me to put (A.S) - allayhis’salaam - after his name, not (R.A) - razi’allah’taala anhu - as Muslims of some other sects do.

Muhammad is, of course, besjdes being the most famous name around the world, also the name of your Prophet (PBUH).

Haider means lion. It was also the title given to Imam Ali (A.S) for his endless courage.

Reza is taken from Hazrat Reza (A.S), the eighth Imam. His name means acceptance.

Rizvi is the surname of the descendants of Imam Ali (A.S).

With all your effort, you made me a symbol of your personal pride, identity, and love for Allah, his Prophet (PBUH), and their historiography. You gave me this title in hopes that you would further the legions of Islam, and raise a boy with the courage and the love for Allah espoused by those you named me after. All this is to say, I understand why you were so shocked when I came out to you as an atheist.

I remember I was once fully a Muslim. I remember as a five-ish-year-old, I’d stand next to Baba while he stood on the janemaaz, and prayed. I’d copy his choreography, mumbling incoherent Arabic without understanding what he and I were really saying. I’d sit on your lap during majaalis, and see you bawl. “There must be something painful and dreadful in these stories of war the old screaming man is telling me,” I would think, my own eyes dry. Baba would tell me waqiat - events - from the Battle of Karbala while I went to sleep. I yearned to have my first roza - fast - in Ramzan before it was made mandatory. I recited nohay for my school in Muharram that you had me memorize: “Abbas meer-e-karwaan”; I’m not sure what this means, honestly. Even back then, I did not know.

My realization of being an atheist did not come with any great reckoning either. But changing my life around these newly held ideas came with pain. “Those who don’t pray namaz go to Hell.” I remember hearing from everyone around me. I remember also when I was fifteen, I watched you shed tears of pride as I wept over the janemaaz. You were filled with pride for how close your son was to God. But my tears were not for God, Ammi. I was fifteen. I was convinced I would go to hell and burn. Today, even as I don’t believe in Hell anymore, the fear of burning remains.

And I don’t pray anymore either, Ammi. Each time I tell you I did; each time it’s a lie. But I don’t like lying to you. So I’m trying to tell you the truth. Even though these words may never reach you, Ammi, I will nonetheless try.

**

Here’s how I remember it happening. It was somewhere around 2017, I was fifteen. I was on my computer, when Baba called me into the living room. He asked me if I knew anything about the Battle of Karbala, or even if I could simply just name the twelve Imams. I nodded No, I knew none of this. Disappointed, you told me to go watch videos and learn this history, what you considered to be our history. I really did not want to, but I went to my computer and opened up videos about the battles, and as usual, I lost my breath.

I started crying, and choking, as the zakir in the videos tore his throat up screaming the waqiat. I paused the video eventually, and even though everything in my body was telling me I was a bad Muslim and an even worse son for crying, I couldn’t help it. I walked, defeated, to the TV room. You were sitting there with my sisters. Our newest family member - a baby girl - was asleep with Baba.

I sat next to you, and you asked if I was watching the videos. I remained breathless for a while, and eventually I managed to say that I wasn’t, and I couldn’t anymore. You asked me why. But I couldn't make my mouth move to form the words: “I am an atheist”, or even “I am an agnostic”. Eventually, I said that I’m an agnostic theist (which was a lie - I wanted to test the waters for whether it was safe to declare the truer yet more transgressive declaration: that of “apostasy” or being a “kafir”.)

I can’t recount exactly how it went down; not because I don’t remember, but because I have blocked most of that memory. But I do remember that you and my sisters told me at length that my thoughts and beliefs were wrong, and they were not welcome in our family. I was telling you how being a Muslim made me feel; and you told me I was wrong to feel what I did. I told you the reasons I didn’t believe in any absolute knowledge of a God. Immediately, you responded, telling me I was wrong to believe what I did.

To you, then, I was a bad Muslim, and a dissappointment. For many nights after that, I didn’t sleep. But for a month after, I still prayed - appeasing the family was more important than being able to breathe.

**

And I wasn’t only a Muslim, I was a Shi’a. I was a Syed. I don’t think I’ll ever forget the memory of you — red-faced, weeping in front of the television on an afternoon in 2009. It was Ashura, the day of Imam Hussain’s (A.S) death, and anti-Shia terrorists had attacked the juloos on M.A Jinnah Road. Baba was at the juloos and wouldn’t pick up our calls. We were afraid he was killed. He wasn’t; he was fine. But the fear stayed with us for years.

In Pakistan, many attacks on Shi’as grew in the following years. Uncles, cousins, and friends were killed for yelling Labbaik ya Hussain (A.S) - “I am here, O Hussain (A.S)”. For the longest time, I was fearful of pronouncing myself as a Shi’a, and yet the courage you’d taught me of meant I was always going to step over that fear and hold my identity proudly. I cried, of course, but I held my head up high.

But you know what was weird? (Please understand this, Ammi: I don’t hate you for this, but what I am about to recount deeply upsets and enrages me) When similar attacks happened on Apostates, Ahmadis, or the Queer community in our own Karachi, Ammi, you had no tears to shed. It makes me wonder; if I wasn’t your son, would you have the same compassion given I was at the end of a bullet? If a gay man was killed in Karachi, would you cry in front of the TV?

What’s also sad is that I can’t uphold the courage you taught me of, towards being an Atheist. The same courage you taught me to hold my identity as a Shia proudly with. For you, a murdered Shi’a would be a shaheed - martyr; but an atheist murdered… that could very well be insaaf. Justice.

**

Once, all my friends were Muslims. As a good Muslim among good Muslim friends, I was to visit established praying areas in school and pray. I was not allowed to show weakness in front of other boys, so I held my tongue when I was tempted to cry. My friend, Rohail, at one point, told me that in the Prophet's (PBUH) Hadith, it says that a wife who says no to entering her husband’s bed will be shamed by the angels all night. He was saying it as a matter of fact, as if it was something to hold pride in. Rohail has a girlfriend today; maybe it’s overly presumptuous of me, but this scares me.

But unlike then, I know many more atheists now, Ammi. There’s almost a temptation to declare that “I won!” out loud. I’m sorry for that, but I can’t help feeling happy with a sense of acceptance in having found people who agree with me.

I remember my time as a Muslim with delusion now. There’s no pride, there’s just sadness that I and those around me didn’t know what we believed in. There was a point in time where with joy, I would’ve talked of Salman Rushdie as the devil. I’m so sorry Ammi, he’s one of my favorite writers today.

I remember hearing about Ayaz Nizami on the TV with you. Ayaz Nizami, the apostate criticizing Islamic beliefs, who was accused of blasphemy. Today, he is on death trial for his opinions, which have been declared crimes. I went through his website, Ammi, it was all just respectable, genuine, engaging criticism. On Twitter that day, the hashtag “#HangAyazNizami” was trending, with posts actively calling for his immediate death. You told me he deserved it. Afraid, I stayed quiet.

**

Ammi, I’m sure you’re wondering what went “wrong” with your son. Unfortunately, there’s no great story of grief, trauma and loss I could tell you that would elicit pathos, and make this story easier for you to handle and me to tell. It’s just this, in the end: I saw some videos on YouTube when I was fifteen which challenged the notions I was raised with and held with utmost conviction. The videos made good arguments. I realized that I don’t believe there is a God.

If I could structure this story the way I wanted, I’d construct it as an escape from reality. This then, would be the plot beat where the maternal figure in the story gets over certain prejudices, and shows her son acceptance despite who he is. But this, unfortunately, is not such a story. There’s no dramatic call to adventure here, and no atonement. So to this day, (I am eighteen now), you tell me I’m wrong to hold these beliefs and it causes you worry and disappointment that I don’t believe in your ideas. You tell me that you might have to go to Hell for the crimes I’m committing. You often tell me about how greatly it worries you, the keera - parasite - in my brain. To this day, you force me to pray. I almost never do.

And you know what else I hate about our story, Ammi? That it doesn’t have an ending. Tomorrow, I will lie about praying once again. If I end up publishing this, I will likely change mentions of my name. Yes, reader, the name you read above isn’t my real name. That’s just because I don’t wish to be another Ayaz Nizami. ‘Ayaz Nizami’ itself, was a pseudonym for the man in question — Abdul Waheed.

At the end of the day, Ammi, you are the person who has seen me through every day of my life, and has made sure I am happy very often. So none of this is to say I hate you. Hell, I even understand that in the world you come from, the ideologies I hold are evil. None of this is to say you are a bad person for holding your beliefs. I understand you, and I love you. I always will.

I just wish I could get - not even complete acceptance - but some of the same understanding from your side.

Aap ka, Syed Muhammad Haider Reza Rizvi*

*This is not the writers real name

Mangal Media is supported entirely by readers like you! Please visit our Patreon page to browse our pledge options and rewards.

Visit our Bookstore

〰️

Visit our Bookstore 〰️

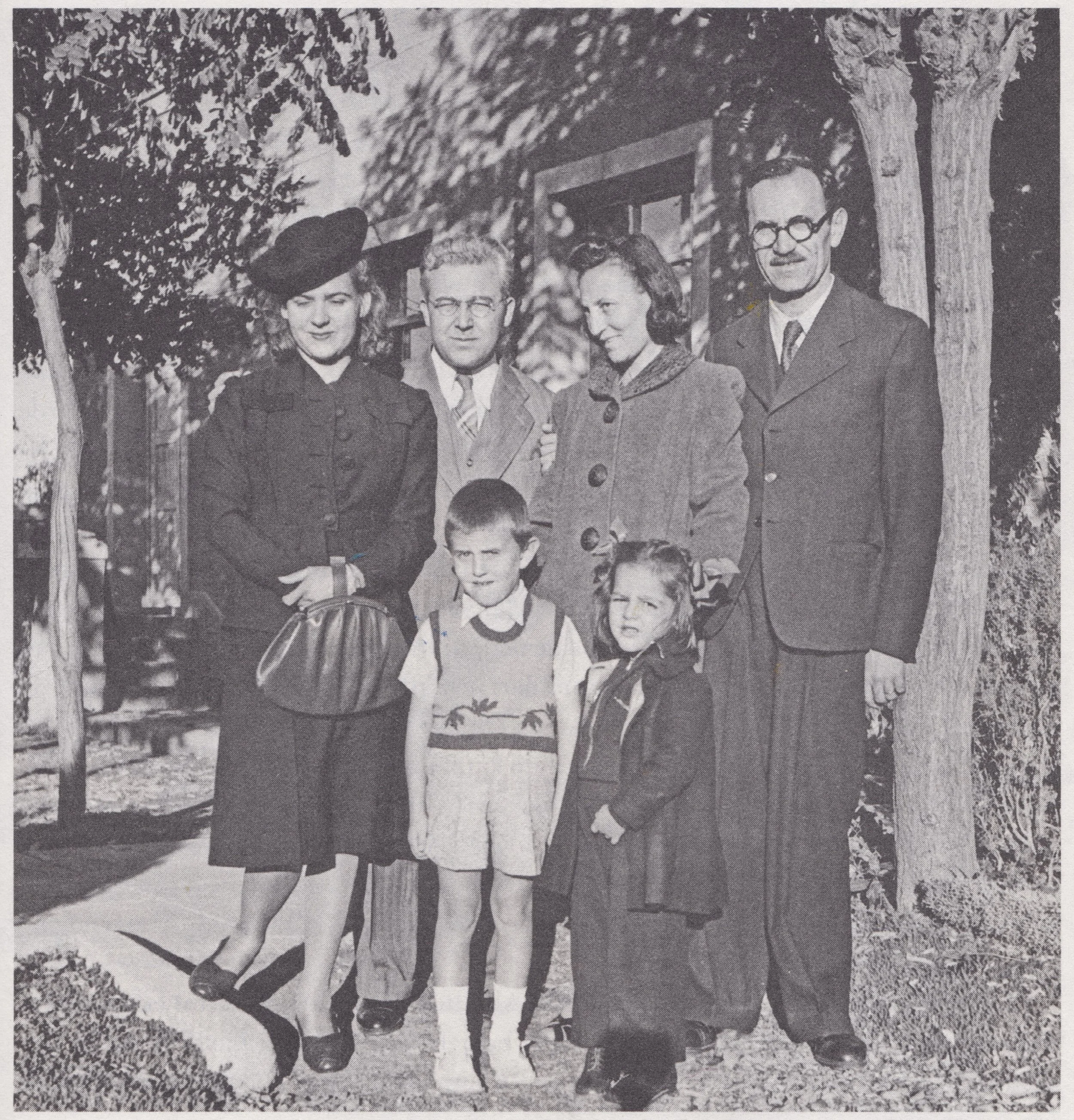

A Letter Home is a deeply personal medley of emotions about Beirut, loss, and dislocation. Ayman Makarem and Hisham Rifai walk a delicate line between yearning and indignation for the home they have left behind. The beauty of this illustrated short story is its bravery in tackling irreconcilable emotions without falling into rose-tinted nostalgia or crippling cynicism. The ease and harmony with which the words and pictures blend together is a testament to the outstanding creative chemistry between Makarem and Rifai.